Steven Parker: The Two Wolves

Steve Parker spent nearly three decades with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department hunting monsters. Gang leaders. Drug traffickers. Organized crime syndicates. He worked in the shadows of society, embedding himself in the darkest corners of the criminal world to protect the people who lived in the light.

But all that time chasing predators took a toll. Somewhere along the way, he lost sight of the man he used to be and started becoming a stranger to himself. He felt it most when he looked in the mirror. There was a man staring back at him, but Parker wasn’t sure who he was anymore.

He felt it most when he looked in the mirror. There was a man staring back at him, but Parker wasn’t sure who he was anymore.

There’s an old Native American parable about a grandfather telling his grandson,

“There’s a war being waged inside of each one of us, a war between two wolves. One wolf is anger, jealousy, hatred, lust, gluttony — all the bad things in the world. The other wolf is love, peace, forgiveness, empathy, trust, happiness — everything that’s good in the world. The two wolves are locked in constant battle, each wanting control of your soul.”

When the boy asked which wolf would win, the grandfather answered, “The one that you feed.”

Years later, Parker heard a song by country artist Cody Jinks inspired by that same story, and it hit him like a freight train. The lyrics felt like they had been written about his own life. One wolf was rage. One was grace. One guarded the door. The other lit the way home. The longer he spent walking the line between both, the harder it became to tell which one was which.

He knew how it happened, though. You don’t just clock out of that kind of job at the end of the day. When your work revolves around threats, violence, and unpredictability, you adapt. You shut down pieces of yourself. You live with one eye open. When your enemies are always watching, you learn to never look away.

At first, Parker managed it. He poured himself into the job and rose through the ranks. He joined a small, elite team working in conjunction with the FBI on Safe Streets Task Force operations. He specialized in dismantling the United Blood Nation, a sprawling East Coast gang network known for its ruthless grip on prisons and street operations alike. He worked cases that spanned from Florida to New York, taking down major players in organized crime. He saw what most people never do — cold-blooded violence, targeted hits, the ripple effects of gang control. In one case, while working with a confidential informant who had once been embedded deep in the gang’s inner circle, Parker received a message that would rattle him to his core.

He worked cases that spanned from Florida to New York, taking down major players in organized crime. He saw what most people never do — cold-blooded violence, targeted hits, the ripple effects of gang control. In one case, while working with a confidential informant who had once been embedded deep in the gang’s inner circle, Parker received a message that would rattle him to his core.

The informant told him that Parker and his wife had been placed “on the menu,” a term used to signify that a hit had been ordered. What made it even more chilling was that the informant himself had been tasked with carrying it out. Instead, he chose to warn Parker.

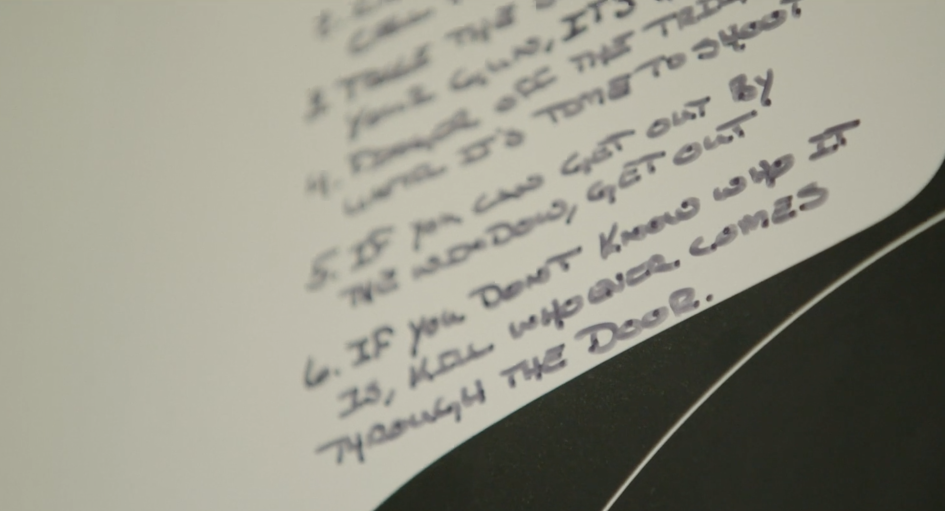

The FBI put the family under surveillance, and CMPD stationed officers near their home. SWAT members lay low in the woods outside their house to keep watch. Parker taught his children how to defend themselves. Other families taught soccer, but he taught survival.

The job had always followed him home, but now it was breaking through the front door.The hyper-vigilance that once made Parker so effective on the job became all-consuming. He couldn’t sleep, relax, or connect. His wife Cheryl — affectionately called Babs — tried to reach him, but he was already slipping away. “You’re here, but you’re not here,” she told him. The man she married had become a ghost in his own home.

Parker spiraled. He withdrew from his family, then from his teammates. He began to isolate, drinking heavily when he traveled for work, hiding behind the badge he once wore with pride. His kids started asking which version of Dad was coming home.

Then came the night he couldn’t pretend anymore. He told Babs he was heading to the gym but never made it out the door. Instead, he walked into the bedroom, collapsed face-first on the bed, and began to sob. When Babs asked what was wrong, he finally admitted, “I don’t know what is wrong with me.” It was the first honest thing he’d said in months.

That moment broke something open. Over time, Parker began to talk. He opened up to a fellow ATF agent named John, who encouraged him to journal. It wasn’t about being eloquent; it was about putting words to what was eating him up inside. He began to write down the memories he couldn’t shake, the guilt he didn’t know what to do with, the things he was too afraid to say out loud. He confided in Babs, his children, and his partners. He started confronting the memories he’d buried, and the shame that came with them.

He remembered the night he nearly ended his life, weapon in hand — a moment he carried alone for a long time before ever speaking it aloud. He was stopped only by a single, jarring thought: They’ll never get my blood out of Babs’s clothes.

It wasn’t long after that when his department stepped in. They had seen the warning signs — knew the toll the job could take — and signed on for a program called Struggle Well through the Boulder Crest Foundation, an initiative designed to help veterans and first responders process trauma and find purpose through Posttraumatic Growth.

Initially, Parker didn’t want to go. But what started as a reluctant two-day training turned into a lifeline. He joined a cohort, sat through the first day, and lied when asked what he was struggling with. Then, as others opened up, something inside him cracked. Honesty flooded the room, and Parker let it flood him, too.

“Everyone has their Rolodex of answers, just waiting to drop a quote or a cliché,” he said. “But none of that helps. What helps is sitting there. Listening. Letting people talk without trying to fix them.”

Struggle Well gave Parker the language and principles to guide him. It taught him how to live again, not as a fractured version of himself, but as someone integrated, aware, and whole. It showed him that the two wolves inside him, anger and grace, shame and growth, didn’t have to tear him apart. He could choose which one to feed. And perhaps more importantly, it gave him Babs back. The woman who had stood beside him in the darkness now stood with him in the light. Through the framework of Struggle Well, Parker began to communicate again. To reconnect. To repair what had been broken — not perfectly, but honestly. Their marriage, once on the brink, grew stronger.

And perhaps more importantly, it gave him Babs back. The woman who had stood beside him in the darkness now stood with him in the light. Through the framework of Struggle Well, Parker began to communicate again. To reconnect. To repair what had been broken — not perfectly, but honestly. Their marriage, once on the brink, grew stronger.

His children noticed the difference, too. They saw a father who was present, emotionally and spiritually. One who apologized, who told the truth, who chose to fight for himself the way he had always fought for others. And now, with the arrival of his first grandson, Parker has the chance to pour into the next generation from a place of wisdom, clarity, and peace.

Struggle Well gave him a renewed sense of purpose just as he stepped into retirement. “I had no idea how I was going to handle retirement,” he said. “But this… this is it. This is the next mission.”

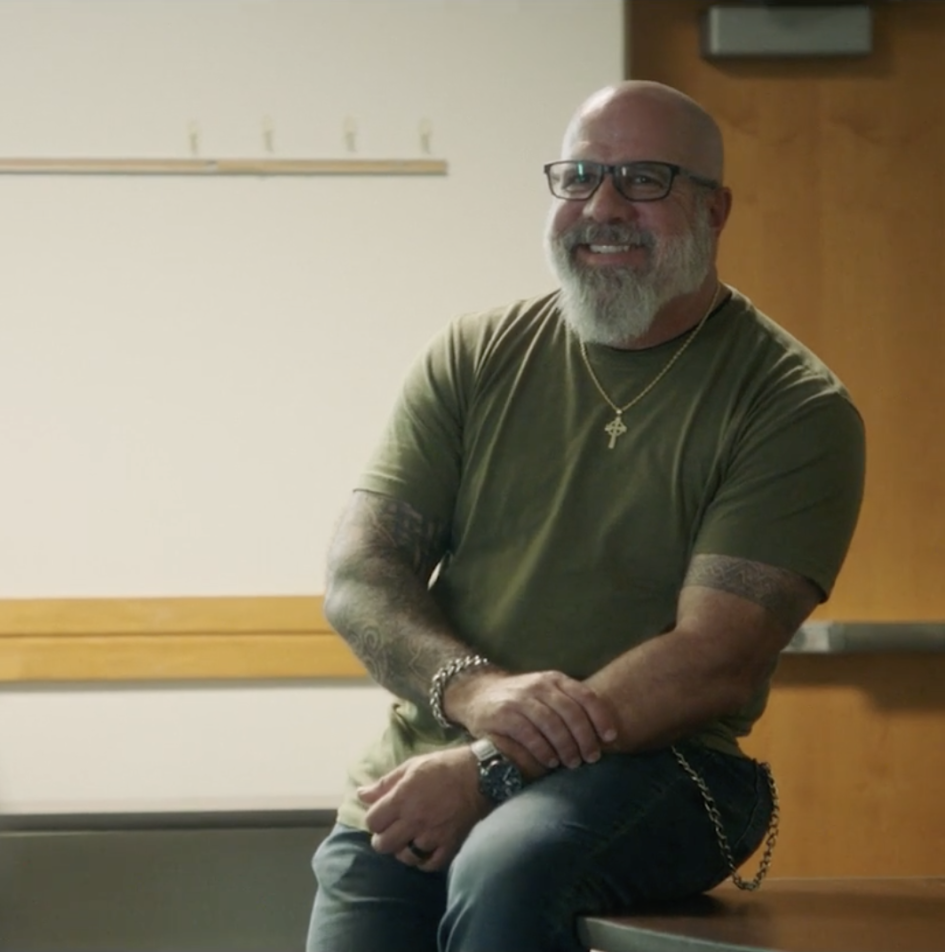

Today, Steve Parker is a Struggle Well trainer. He stands before rooms of veterans and first responders, not as someone who has all the answers, but as someone who knows what it means to fall apart and to be put back together.

He teaches them how to feed the right wolf.

When he looks in the mirror now, he sees something he never thought he’d see again:

A man he recognizes. A man he respects.

If you or someone you know is a veteran, active-duty military, or first responder struggling with trauma, depression, or anxiety, learn more about Struggle Well and Warrior PATHH programs designed to help you grow through what you go through.

Continue reading more about Posttraumatic Growth in our resource library.

PTG Resource CenterYour support powers life-changing programs offered at no charge to veterans, military, first responders, and their families. With your help, our Warriors won't just survive — they'll thrive.

We have received your email sign-up. Please tell us more about yourself.