Brian Wilson: Out of the Dust

The dust never settled in Ramadi. It clung to everything—skin, lungs, gear. It thickened the heat and blurred the lines between sky and street, between enemy and civilian. It wasn’t just the dust that made it hard to breathe. It was the knowledge that any road could be wired with death.

In the spring of 2006, First Lieutenant Brian Wilson was 24 years old, leading a rifle platoon of 42 Marines through what Dan Rather once called “the most dangerous city in the world.” Ramadi was kinetic, volatile, and unforgiving. Thirty days into deployment, Brian took his unit out on their first vehicle-mounted patrol through the city. He knew the threats. He’d studied the routes. He had avoided a road called Racetrack for weeks—a notorious stretch vulnerable to buried explosives—but that morning, every route out turned into an alley. Every turn, a dead end. With nowhere else to go, the convoy turned onto Racetrack.

He knew the threats. He’d studied the routes. He had avoided a road called Racetrack for weeks—a notorious stretch vulnerable to buried explosives—but that morning, every route out turned into an alley. Every turn, a dead end. With nowhere else to go, the convoy turned onto Racetrack.

Six vehicles stretched across two city blocks. Tall buildings flanked them, windows gaping open like dark mouths. Brian’s truck was second in the column. The first vehicle made the turn. His followed. And then—

The last vehicle never made it.

An IED—three 152mm artillery shells packed with diesel fuel and sealed beneath a manhole cover—detonated directly beneath the sixth truck. The blast obliterated it. Only one Marine survived the explosion. One was thrown onto a rooftop nearly a block away.

That was April 2, 2006. The worst day of Brian’s life.

Four Marines from his platoon were killed in that single incident. Thirteen Purple Hearts would eventually be awarded to the men under his command. Brian earned one of them.

“It set in motion who I am,” he said. “But for years, I only understood that through the pain.”

Back home, he traded the streets of Ramadi for the baseball fields of Virginia. But the dust didn’t stay behind. The nightmares came first. Then the insomnia. Then the ever-present sense of danger that followed him into civilian life.

“Trauma cuts both ways,” Brian said. “It teaches you how to survive, and then it dares you to try and live.”

For years, hypervigilance ruled his life. He’d wake up to alarms he set on purpose to interrupt nightmares. He’d coach his son’s baseball team while instinctively scanning for exits and escape routes. But there were also times when that vigilance was a gift.

Wilson calls it “the gift of fear,” borrowing the phrase from Gavin de Becker’s book of the same name. “I notice things other people don’t. That’s part of it. And I’ve learned how to use that, not just let it use me.”

There was a time, though, when even those instincts couldn’t ground him.

In 2019, Wilson found himself in a dark place. He was sitting on the couch of his home outside Atlanta, struggling silently, when a wave of despair hit. While he doesn’t often recount every detail, he has shared that one small, domestic thought kept him from making a permanent decision: his wife would be the one to find him.

A year later, in August 2020, he attended the funeral of Sergeant Thomas Moss, a Marine from his Ramadi platoon who had survived the war—but not the aftermath. It had been nearly 15 years since they’d all seen each other. At the service, Brian sat behind a little girl who kept turning around to smile and wave at him. She eventually climbed into his lap and played with the medals on his chest.

“She sat with me for 20 minutes,” Brian recalled. “I didn’t know until later that it was Thomas’s daughter. And what she saw on my uniform reminded her of her dad.”

He drove away from that funeral with a decision: “You’re going to widow your wife and leave your son like that little girl, unless you do something different.

“Sergeant Moss was this young man, who in many ways, in many firefights, did things that saved my life as a 24-year-old—and he saved my life again.”

Two months later, during a routine screening, he found the courage to say the words out loud: “I don’t know what PTSD is, but I’m pretty sure I have it. And I want help because I don’t want to kill myself.”

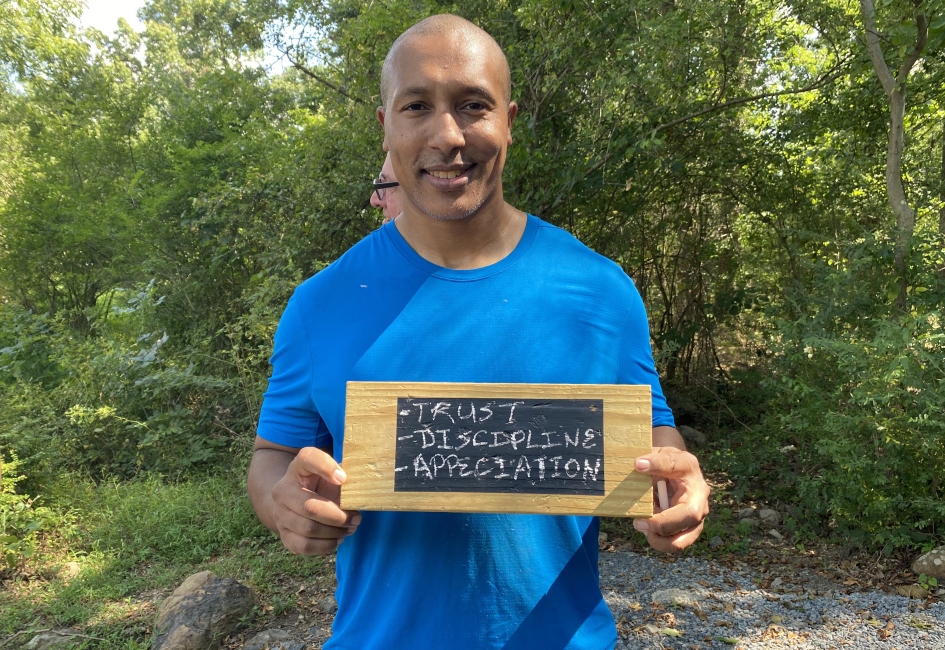

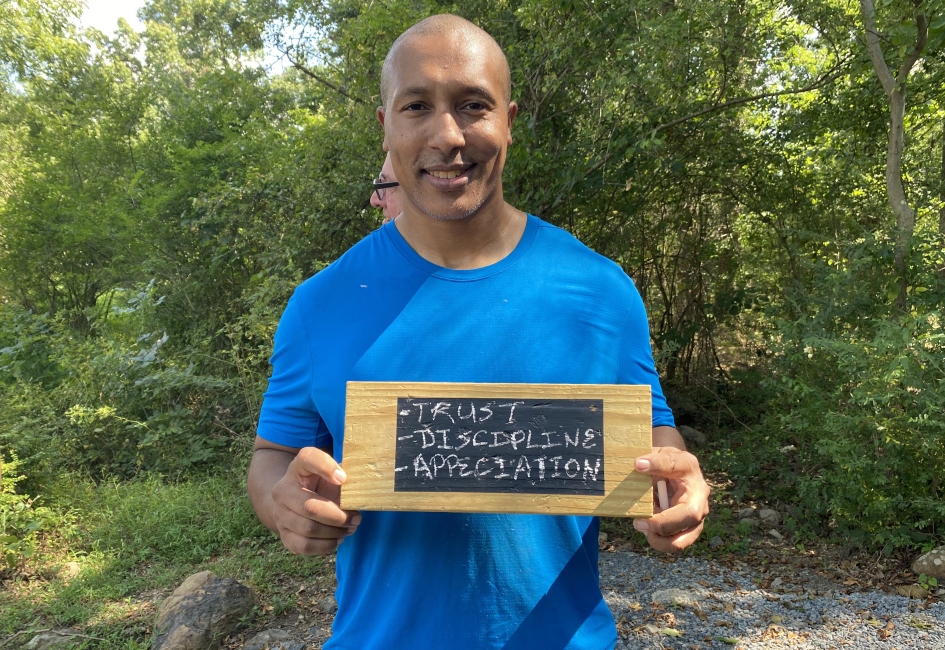

That moment cracked the door open. The next year, Brian enrolled in the Warrior PATHH program at the Boulder Crest Foundation, a transformative experience built on Posttraumatic Growth. “I always caveat this by saying Boulder Crest wasn’t my only saving grace,” Brian said. “But it introduced me to the idea that I could live the life I wanted. I didn’t have to just survive.”

“I always caveat this by saying Boulder Crest wasn’t my only saving grace,” Brian said. “But it introduced me to the idea that I could live the life I wanted. I didn’t have to just survive.”

Warrior PATHH challenged everything he thought he knew about himself. It forced him to slow down, to sit with his emotions, to see his vulnerability not as a weakness but as a superpower.

“I make a decision every day to be still. And when a moment comes where I need to be still and it doesn’t feel natural, I can go back to that place. I can calm myself.”

He learned how to meditate. How to breathe. How to let go. He learned that the same instincts that once kept him alive in combat could serve him in fatherhood, in marriage, in coaching Little League.

“If you had met me four years ago and told me I’d be meditating, I would have laughed at you,” he said. “Like, no, I’m not meditating. But it has changed my life because it forces you to pause. I’m not looking back, and I’m not looking forward—I’m living in the moment.” His wife sees the difference. She knows when he hasn’t been meditating. She sends him to Boulder Crest’s retreat in Bluemont to volunteer and spend time in the space when she senses he’s drifting. And every time he comes back better. Calmer. More grounded.

His wife sees the difference. She knows when he hasn’t been meditating. She sends him to Boulder Crest’s retreat in Bluemont to volunteer and spend time in the space when she senses he’s drifting. And every time he comes back better. Calmer. More grounded.

“She tells me, ‘I can always tell when you’ve been up there. You’re better. You’re different.’”

Boulder Crest didn’t erase the past, but it helped reframe it. It gave Brian the practices to transform his pain into purpose, and a path forward that honors both the battles he fought and the man he’s become.

Now, when the dust stirs—whether in memory or in the quiet moments of daily life—he knows how to pause, breathe, and brush it gently off his shoulders.

“I’ll never stop being a Marine,” he said. “But I don’t have to stay in the fight forever. I get to be here. I get to live.”

Your support powers life-changing programs offered at no charge to veterans, military, first responders, and their families. With your help, our Warriors won't just survive — they'll thrive.

We have received your email sign-up. Please tell us more about yourself.